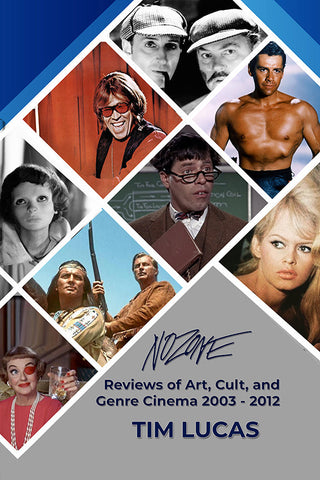

Tim Lucas Q&A on his new NoZone book

Tim, could we start with you telling us something about your new book NOZONE, in general?

Certainly. NOZONE collects all of the “NoZone” review columns that I wrote for SIGHT & SOUND, the magazine of the British Film Institute, between 2003 and 2012 - so, a nearly ten-year period. My editors there, Nick James and James Bell, were exemplary at their jobs. James Bell, in particular, was personally assigned to the column and always made the end result a bit better than what I initially turned in. I’ve always been bad with numbers and could never turn in the word count that was asked for. So James sometimes had to cut or reduce closing paragraphs, tighten my synopses, or decide which details were most expendable. In preparing this book, I compared each column to my original drafts and reinstated details or observations that were trimmed for publication, while also preserving the improvements brought to my text by editing. I was aware at the time that writing for such an esteemed magazine, having the privilege of addressing its readership, and working with such talented editors and fact-checkers was raising my game. I honestly feel this body of work is among the best I’ve done.

What’s the meaning of the title NOZONE?

Good question! One of the things my magazine VIDEO WATCHDOG innovated was coverage addressed not to people with a casual interest in film, but people who were genuinely obsessive about film, who didn’t let anything stand between them and whatever they wanted to see. Other film magazines at the time just reviewed what was released in their own territory. Though VIDEO WATCHDOG was published in Cincinnati, Ohio, we had readers all over the world who sent us information about what was coming out in England, France, Germany, and even Turkey! So some of us who wrote for the magazine acquired the first region-free VHS players, like the Panasonic AG-WI. This allowed different countries to communicate and compare how films differed from country to country - not just in terms of video quality, but also in matters of content. So I became identified with this outreach.

When I was first approached to write the column by James Bell, I was told they wanted me to cover the most interesting new home video releases being released anywhere outside their main turf, which was the UK, where Region B or 2 players ruled. They knew there was a burgeoning portion of their readership that had multi-region players and that more and more of their readers were looking for information and guidance about what was available outside their “zone,” so to speak. Hence, “NoZone.”

So the unifying theme of this book is all down to region codes?

Technically, yes… but mind you, within that guideline I was allowed to follow the compass of my own tastes and curiosity. There were times when a specific title was suggested to me, but they generally acceded to my own preferences. In the earliest entries, you’ll see that I started out trying to cover more than one release per column, but I soon found this was preventing me from digging more deeply into the material, so I was soon allowed to focus on single titles, which is where the column found its identity.

You wrote these reviews at what must have been an incredibly busy time in your life. How did you manage?

Well, when you must, you do. There’s an old saying with a lot of wisdom in it: if you need help to get something done, ask a busy person. At the time I was writing the NOZONE column, I was also reviewing and editing VIDEO WATCHDOG, I was blogging at VIDEO WATCHBLOG, and I was also writing MARIO BAVA - ALL THE COLORS OF THE DARK between issues of VIDEO WATCHDOG, which—at some point during all this—became a monthly magazine out of monetary necessity! I remember the good Kim Newman coming to our rescue and taking some of the load off my shoulders during that hectic time. The Bava book came out in 2007, and then in 2012—as I was still doing VW, the blog and NOZONE—I had the insane idea to add to my workload by starting up a second blog called PAUSE. REWIND. OBSESS., where (as an experiment) I literally reviewed at length every film I saw in that year. A collection of all my P.R.O. reviews is coming out soon from Bear Manor Media. These two books share some of the same time period in my work, with P.R.O. coming into being as NOZONE was starting to wind down.

Your subtitle describes your coverage in this book as “Art, Culture and Genre Cinema.” Because of your early work for CINEFANTASTIQUE, FANGORIA and GOREZONE, and then VIDEO WATCHDOG, you’re mostly associated with horror and fantasy films. Did NOZONE cause a broadening in your work?

Horror and fantasy are what initially attracted me to films. But, as a kid, I read CASTLE OF FRANKENSTEIN magazine, which was ostensibly about horror and monsters but also embraced mention or discussion of directors like Orson Welles, Jean Cocteau, Max Ophüls, Ingmar Bergman, Alain Resnais, Georges Franju, and Henri-Georges Clouzot. Not to mention Mario Bava! So, once I reached a certain age, I began seeking out the work of filmmakers beyond the narrow scope of Universal and Hammer horror, and I discovered all of these filmmakers and others by my mid-teens. So when my wife Donna and I started VIDEO WATCHDOG, I wanted to bring that broader range of awareness into our coverage. So we called it “The Perfectionist’s Guide to Fantastic Cinema” rather than something more singularly obsessive about any one genre. All that we asked of a film was that it “astonish us” in some way, as Cocteau said.

When I started doing audio commentaries for DVDs and Blu-rays, around the turn of the century, I was asked to do them only for Mario Bava films and other horror titles, but Bret Wood (a producer at Kino Lorber) had been an occasional VIDEO WATCHDOG contributor and knew I had potential to comment effectively on other kinds of films. Thanks to him, I’ve been able to do commentaries on films like LAST YEAR AT MARIENBAD, ALPHAVILLE, THE NIGHT OF THE HUNTER, and THE LADY FROM SHANGHAI, as well as Sergio Leone’s “Dollars Trilogy.” It was because of an essay I wrote for my blog that James Blackford (then of the BFI) invited me to do the commentaries for an entire box of films by my literary hero, Alain Robbe-Grillet. More recently, James asked me to do commentary for John Frankenheimer’s IMPOSSIBLE OBJECT for Powerhouse/Indicator in the UK.

So, in answer to your question, the broadening was already there and, though I had to run my choice past my editor before writing anything, as long as there was no conflict of assignment on a given title, I was given absolute freedom. NOZONE includes coverage of some horror films, but it offers a pretty broad assortment of genres.

Are there other film critics you read for insight, entertainment, companionship?

I did when I was younger and first getting my bearings, yes. My most important formative reading was HITCHCOCK/TRUFFAUT and also Ivan Butler’s book HORROR IN THE CINEMA with its remarkable analysis of Roman Polanski’s REPULSION. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve had the experience several times of discovering and adoring marginal or derided filmmakers whom I avoided for decades because other critics had biased me against them or their kind. Nowadays, I’ll give most things a chance but not new horror movies. Horror films are not what they used to be, and I’ve long since stopped bothering to see everything, so I rely on what friends and colleagues like Kim Newman and Stephen R. Bissette (who see everything) may say on social media.

I do and will read film history, though, and tend to think that proper film historians—not the ones who just repeat what they’ve read from other people’s work—are much more important than film critics. With me, it’s like… For example, I’ve often heard musicians say that they actually listen to very little music other than what they are working on, themselves. John Lennon’s personal jukebox contained only his favorite records from the 1950s. That’s what got him going, and he didn’t need anything else, least of all his competitors. Whether or not you like John Lennon’s music, there is a purity that runs through it, and it’s because he took care not to fall in love with other people’s music.

Since I found my own voice as a critic, the most important critical writing I’ve found has been addressed to literature and music. I’ve learned as good deal more from John Updike’s compendiums of his critical writings (like PICKED-UP PIECES, ODD JOBS and HUGGING THE SHORE) or Richard Cook & Brian Morton’s THE PENGUIN GUIDE TO JAZZ than I’ve ever gleaned of real use from other people’s film criticism. Reading novels, too, will make someone a better critic than reading other people’s criticism, because novels will help you bring something warm and human and humorous to your considerations. I don’t waste anyone’s time by mimicking what’s good out there, nor do I want to waste my time on what’s not. I basically write criticism as a kind of inverted analysis of myself. I do it to dig deeper into what I think; I do it to get past the superficial; I do it to learn.

For those readers who faithfully read these columns as they appeared, are there any surprises in the book?

Some. More than a decade has passed since these reviews originally appeared. It wouldn’t have been right to repackage them untouched, so I’ve updated the information pertaining to current home media availability in each case. I’ve mentioned when past problems have been corrected. I also went back to my original submission drafts, which sometimes had to be cut for length, and put back whatever seemed pertinent or valuable, while at the same time preserving the improvements brought to bear by my original editor. There was also one case where I proposed a film I wanted to cover, which another S&S contributor had already claimed. This was Tom Six’s THE HUMAN CENTIPEDE (2009). I decided to review the film anyway and file it away, and it makes its first-ever appearance in the book.

What do you look back on as the highlights of your NOZONE experience?

In terms of the highlights of its content, the big ones for me were my reviews of Jonathan Weiss’s THE ATROCITY EXHIBITION and Lech Majewski’s THE GARDEN OF EARTHLY DELIGHTS (2004), both of which were small, under-the-radar films that I believed were masterpieces of cinema, and still do. The Weiss film achieves the impossible in filming a reputedly “unfilmable” novel, giving us a more accurate representation of Ballard than we get in, for example, David Cronenberg’s CRASH (1996), which—regardless of many people’s aversion to its subject matter—is still a somewhat glamorized representation of the book. THE ATROCITY EXHIBITION is a far more difficult, experimental book than CRASH and I found watching the film to be a very liberating experience; it wasn’t setting out to recoup many millions of dollars of investment. It was just being what it was, boldly and proudly, which I found much more liberating for its medium.

THE GARDEN OF EARTHLY DELIGHTS is an extraordinary original work, based on a novella by the director, in which a sail-maker and a museum guide with a special interest in Hieronymus Bosch fall in love and have an affair, which coincides with the woman (played by Claudine Spiteri) learning that she has terminal cancer. The two of them decide to take an apartment in Venice where, in anticipation of her transition, they set about transforming their living space into life-sized details from the famous Bosch painting, the two of them recreating the strange and erotic interactions depicted within it—a kind of mutual escape from life into art. It’s a towering work of art, that film, and it was entirely shot on the equivalent of a telephone. It proved to me that the most important thing anyone can bring to a film is its idea, but that idea must have autonomy. It needs that purity I mentioned earlier, and it’s not likely to find it, the way things are set up in film production today. By the way, in NOZONE I also review Majewski’s 2011 film THE MILL AND THE CROSS, with Rutger Hauer, which takes the viewer on another deep dive into a classic work of art, in this case Pieter Brueghel’s Flemish masterpiece “The Procession of Calvary.” It’s a film that actually teaches the viewer how to see.

Could you name a handful of movies that taught you “how to see”?

Seeing Sergio Leone’s ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST (1969), when I was about 13, was an event. It taught me the difference between movies and cinema: in movies, it’s the dialogue that’s important; in cinema, the images are important and the dialogue is gravy. I remember staggering out of the theater, feeling physically changed by that experience. Federico Fellini’s TOBY DAMMIT (1968), which I first saw around the same time, showed me how a film could be simultaneously baroque, expressionistic, impressionistic, horrific and beautiful, hallucinatory, and even contemporary in telling a story written in a past century. When I was much younger, in late 1963, I got to see Ronnie Ashcroft’s THE ASTOUNDING SHE-MONSTER (1958) in 35mm on a big screen—the same screen as both of the other films I just mentioned, in fact. This is a much lesser movie, obviously; it’s essentially a movie about people who are outside and go inside, then they can’t stay inside so they go outside, then they have to go inside, then back outside, and then inside again. I would have been seven years old at the time, but I could already tell that I was learning something about (to use adult terms) minimalism, dream logic, and the willing suspension of disbelief. I was profoundly moved by that film as well, and for a long time I watched it once every year. I still want to write something about it. Then there were certain movies I only saw as an adult, like Alain Resnais and Alain Robbe-Grillet’s LAST YEAR AT MARIENBAD (1963), which I especially love because it’s a self-sufficient work of art that makes no reference to anything outside its own enclosed sense of reality. Well, almost… Resnais added an Alfred Hitchcock cameo to the film, which most viewers never notice, and I think it’s the only flaw in the picture. I suppose if it didn’t have this, it could be an affront to God.

What are you working on now?

I’m just now waiting to approve the cover of my next Bear Manor Media book, which will collect all of the entries I wrote for a (now-deleted) blog called PAUSE. REWIND. OBSESS. At the end of 2011, I saw friends on social media sharing lists of all the movies they saw that year. I had never thought of actually keeping lists of such things. So, even though my hands were full with other things, I had the idea to not only list, but actually review in detail each film I would see in the new year of 2012. I expected to write thumbnail reviews, but they were usually at least three paragraphs long. I wrote them all faithfully but in haste, so, when I took the blog down, I began revising each of the reviews to bring them up to my best standards. So that’s is the next book. I also have a monograph on Jess Franco’s film SUCCUBUS (Necronomicón, 1967) forthcoming from Electric Dreamhouse/PS Publishing in the UK, and my novel THE ONLY CRIMINAL will be published by Riverdale Avenue Books’s “Afraid” imprint later this year. As for present work, I’ve been doing a lot of audio commentaries for different companies here and abroad, and I’m also writing a book about Joe Sarno, an “Adults Only” filmmaker of the 1960s and ‘70s who achieved some wonderful things in a maligned genre, which I’d like to see in print next year.